Provides a foundation of Object-Oriented Design principles in JavaScript.

JavaScript is a class-less, object-oriented language. A good understanding of OO Design, SOLID, and DRY Principles is required to be able to build web apps with Design Patterns.

JavaScript is a class-less, but object-oriented (OO) language. Objects are a core concept in JavaScript and as a JavaScript developer it is important to have a good understanding of OO principles and rules. In this section we review object oriented design and programming techniques including SOLID and DRY principles -- all in the context of JavaScript.

First we examine the fundamental characteristics of OO; they are data encapsulation, data abstraction, inheritance, and polymorphism. After that we review the terms loose coupling and high cohesion which describe the relationship between objects and their interdependencies. You will learn what all these concepts mean to JavaScript development.

SOLID is an acronym that stands for five object-oriented principles that are considered essential in good object-oriented design. We will examine each of these and their relevance to JavaScript.

Finally we present the DRY rule (Don’t Reply Yourself) which states that no code duplication should be allowed. However, 'keeping your code DRY' should not be taken too literally as explained by the Rule of Three which states that sometimes limited duplication is acceptable.

We will start off with the 4 OO design characteristics: data encapsulation, data abstraction, inheritance, and polymorphism.

Data Encapsulation

Data encapsulation is the hiding of data in your objects by restricting access.

In JavaScript data is stored in properties which is immediately accessible, such as employee.name or via a couple of getter and setter methods,

such as employee.getName and employee.setName.

By the way, these methods are called accessor and mutator methods respectively.

Many languages offer access modifiers, such as, private, protected, and public. By placing these modifiers on the object's members (properties and methods) you indicate who can have access to these members. The private modifier does not allow any access from outside the object; protected allows access only by a derived objects, and public allows access by anyone.

JavaScript does not support access modifiers. By default all properties and methods are public, meaning they are accessible by anyone in the program. This is not always desirable, but fortunately, a number of techniques and patterns have been developed over the last few years that allow you to protect and encapsulate the data in your objects. All these are based on the concept of function closure which will be discussed shortly.

The main take-away for now is that data encapsulation is one of the core principles in OO and is also very important to JavaScript.

Here is an example of a JavaScript object that encapsulates name, but it is publicly accessible as are the accessor and mutator methods, getName and setName.

var Employee = function (name) {

this.name = name;

this.getName = function () { return this.name; }

this.setName = function (name) { this.name = name; }

};

var employee = new Employee("Mike");

employee.setName("David");

alert(employee.getName()); // => David

employee.name = "Peter";

alert(employee.name); // => Peter

Run

We can improve on this by hiding name as a variable, called hiddenName, which is then maintained in the function closure. This variable is only accessible via getName and setName.

var Employee = function (name) {

var hiddenName = name;

return {

getName: function () { return hiddenName; },

setName: function (name) { hiddenName = name; }

};

};

var employee = new Employee("Mike");

employee.setName("David");

alert(employee.getName()); // => David

alert(employee.hiddenName); // => undefined

Run

As you see, the variable hiddenName is not directly accessible. We have succeeded in making the name a private member. The concept of closure will be elaborated upon at other places in this package.

Data Abstraction

Data abstraction refers to the development of objects that are abstractions of real world concepts.

This is done primarily by defining an interface (properties and methods) that best represents the item we are trying to model or abstract out.

For example, if we need to create a Customer object, we are interested in their name, contact information, and purchase history perhaps. If, on the other hand, we need to model a new hire, say a JavaScript Programmer, we are more interested in their education, skill level, years of experience, and salary requirements. The interesting thing is that both are people, but we abstract out only what is of interest to us at that time. Here is some sample code for these two cases (without methods):

var Customer = function () {

this.name = "";

this.contact = "";

this.history = [];

};

var Hire = function () {

this.name = "";

this.education = "";

this.skills = [];

this.salary = 0;

};

This process of designing the best object representation is essentially the process of data abstraction. Again, this process also fully applies to JavaScript objects.

Inheritance

There are different ways that objects can relate to each other. In OO these are often referred to as "has a" or "is a" relationships; more formally composition and inheritance relationships.

When an object references another object, this is called object composition because the object "has an" object. Inheritance is when an object derives data and functionality from an ancestor object, in other words, it "is an" instance of an ancestor object. It is important to note that the main purpose of composition and inheritance is code reusability.

Many programmers are familiar with classical inheritance in which a class derives (extends) from another class. By inheriting the class obtains the data and the behavior from the ancestor class. The inheritance chain can get many levels deep, although this is usually not recommended. For example, you may have: button->control->element->object. This chain is 4 levels deep and these objects usually go from generic (sharable functionality) to more specific and specialized.

Inheritance is fully supported in JavaScript, but through a different mechanism, called prototypal inheritance. Each object in JavaScript has a prototype object from which it derives properties and methods. We will get much deeper into prototypes later on, but please be aware that JavaScript fully supports inheritance.

Here is an example of object composition in which a car "has an" engine. All newly created cars will have an engine with 4 cylinders

var Engine = function () {

this.cylinders = 4;

};

var Car = function () {

this.engine = new Engine();

};

var ford = new Car();

alert(ford.engine.cylinders); // => 4

Run

And here is an example of inheritance, where a toyota "is a" car. All toyotas will have 4 wheels and 4 doors.

var Car = function () {

this.wheels = 4;

this.doors = 4;

};

var Toyota = function (color) {

this.color = color;

};

Toyota.prototype = new Car(); // set Car as 'ancestor' object

var toyota = new Toyota("red");

alert(toyota.color); // => red

alert(toyota.wheels); // => 4

alert(toyota.doors); // => 4

alert(toyota instanceof Toyota); // => true

alert(toyota instanceof Car); // => true

alert(toyota instanceof Object); // => true

Run

In the last 3 lines we confirm that toyota "is a" Toyota, toyota "is a" Car, and toyota "is an" Object; essentially the entire inheritance chain.

Polymorphism

The word polymorphism literally means many forms. It is the ability to create multiple objects that to the program appear of the same type but they are different.

This is accomplished by creating objects that have the same interface (properties and methods) but their concrete implementation is very different. Let's look at an example.

Suppose we are modeling different zoo animals: a swan, a monkey, and an elephant. All these animals have a skin and they can move and can talk (make a sound). To model these we create for each an object with the following interface: a skin property and two methods: move and talk. Here are the relevant objects:

var Animal = function (home) {

this.home = home;

};

Animal.prototype = {

say: function () {

alert("I live in a " + this.home);

}

};

var Swan = function (skin, move, talk) {

this.skin = skin;

this.move = move;

this.talk = talk;

};

Swan.prototype = new Animal("pond");

var Monkey = function (skin, move, talk) {

this.skin = skin;

this.move = move;

this.talk = talk;

};

Monkey.prototype = new Animal("jungle");

var Elephant = function (skin, move, talk) {

this.skin = skin;

this.move = move;

this.talk = talk;

};

Elephant.prototype = new Animal("zoo");

Next we create 3 different animal instances and add these to an array:

var animals = [];

var swan = new Swan("Feathers",

function () { alert("I fly"); } ,

function () { alert("Honk"); });

var monkey = new Monkey("Furr",

function () { alert("I climb"); } ,

function () { alert("Ooh Ooh"); });

var elephant = new Elephant("Thick skin",

function () { alert("I walk"); } ,

function () { alert("Trumpet"); });

animals.push(swan);

animals.push(monkey);

animals.push(elephant);

We then iterate over the array and find out a little more about each animal:

for (var i = 0, len = animals.length; i < len; i++) {

animals[i].say(); // I live in a pond, jungle, zoo

alert(animals[i].skin); // Feathers, Furr, Thick skin.

animals[i].move(); // I fly, I climb, I walk

animals[i].talk(); // Honk, Ooh Ooh, Trumpet

}

Run

This demonstrates that although all three animals are very different (for example, the swan flies, the monkey climbs, and the elephant walks). But as far as the program is concerned the interface is the same (they all move, talk, etc.) and can be accessed in the same manner. This is polymorphism in action.

Next we will review the concepts of loose coupling and high cohesion which describe the relationships between objects and their interdependencies.

Loose Coupling

Loose coupling means there is a low degree of dependency among objects.

Loose coupling is a design goal that seeks to reduce the interdependencies between objects with the goal of reducing the risk that changes in one object will require changes in any other object.

Coupling is a measure of how much direct knowledge an object has about another object. The more it knows, the more tightly coupled it is with that object. Tight coupling creates highly interdependent systems that are much harder to change and maintain. Coupling is not limited to objects; it also plays a role at the component level, which in JavaScript equates to modules (discussed in the Modern Patterns section).

Loose coupling can be measured by the number of changes that are required when, for example, a property or method is added or removed from an interface. Or possibly the entire interface of a utility object is changed, how much of the code is affected by this change? Tight coupling is a form of technical debt, which is an obligation that a project incurs when it chooses an OO design that is expedient in the short term but increases the complexity and cost involved in the long term.

The goal of loose coupling is to create systems that are flexible and are easy to maintain. Writing loosely coupled code is not always obvious and requires an experienced designer/architect. Here is an example of an object that requires intimate knowledge of a database. Changing the data model requires a different interface and each client needs to be changes as well.

var db = function () {

function SaveOriginalEmployee(employee) { };

function GetEmployeeBySalary(salary) { };

function GetEmployeesInCanada() { };

function UpdateEmployeeWithSalaryIncrease(increase) { };

function UpdateUserByName(first, last) { };

function DeleteUserById(id) { };

function SelectRecentCustomers(time) { };

// ...

};

Here is a much cleaner data access API that rarely needs change (even when the data model changes or a switch to another database is made):

var db = function () {

function Select(criteria) { };

function Save(object) { };

function Update(object) { };

function Delete(object) { };

// ...

};

High Cohesion

Objects with high cohesion are those that are highly focused and have elements that form a coherent group and they truly belong together.

Cohesion is a measure of how strongly related each piece of code is forming a comprehensive unit of functionality.

Objects with high cohesion are preferred because they are reliable, reusable, understandable, and easier to maintain.

In fact, high cohesion goes hand in hand with loose coupling. Systems that are loosely coupled often have objects that have high cohesion and vice versa. Intuitively this makes sense because if you have a well-designed system in which each objects has a clear focus then their interactions and dependencies with other objects become more clear and succinct creating a high quality OO design overall.

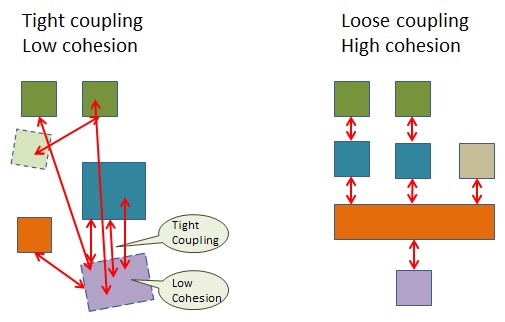

Below is a diagram that depicts the notion of high-cohesion and low coupling. The blocks symbolize the objects and modules. The arrows represent the relationships and dependencies. It is important to note that cohesion exists within objects and modules (the blocks), whereas coupling exists between objects and modules (the arrows).

On the left we have objects that are confused about their exact responsibilities leading to low cohesion and spaghetti objects that are highly dependent on each other, i.e. tight coupling. Making a change to this system, without breaking something else, is a real challenge.

On the right we have a system in which each object has a clear focus and knows its responsibility and role in the larger system. The system is well-organized, easy to understand, and changing an object will affect only a limited number of clients. We have accomplished loose coupling and high cohesion.

Next we will review the SOLID principles of object oriented design. We should point out that there is a fair amount of overlap between the five SOLID principles, the four OO characteristics, and the notion of loose coupling and high cohesion: their common aim is to create better object models.

SOLID is a mnemonic acronym coming from the object-oriented design world. SOLID is a set of object-oriented principles that are considered essential for good object-oriented designs. These principles were popularized in numerous publications by Robert C. Martin.

The SOLID principles do not tell whether a conceptual object model is correct or not, that is, it does not show whether the object model is a good representation of the system being modeled. Instead it focuses on object dependencies and how objects relate to each other. The underlying idea is that when objects and their dependencies are well managed applications will be robust, flexible, reusable, and easier to maintain.

Here are the five SOLID principles (notice the first letters form the word SOLID):

We will go through each in some detail. It is important to realize that these concepts were originally presented in the context of statically typed, object-oriented languages with support for classes. Since JavaScript is a dynamically typed, functional language with support for objects but not for classes, we will cast these principles in terms that are applicable to JavaScript developers.

Single Responsibility Principle

The single responsibility principle states that an object should have one, and only one, reason to exist.

What this means is that an object should have a cohesive set of properties and methods together comprising a single comprehensive responsibility.

When an object has multiple responsibilities and one of those requires a modification, there is the risk of breaking other responsibilities.

Single responsibility greatly improves maintainability.

This is one of the most important principles in OO design; objects that are not clear about their responsibility are bound to cause poorly designed apps. This also fully applies to JavaScript.

Open Closed Principle

The open closed principle relates to the extensibility of objects and states that an object should be extensible without modifying it,

that is, it should be open for extension, but closed for modification. This means that an object should be adaptable to change,

but without touching the existing properties or code in the methods. If the only way to extend an object's behavior is by changing current code,

you quickly risk negatively impacting the existing code base. The Open Closed Principle improves maintainability.

The Open-Closed principle clearly applies to JavaScript. JavaScript library plugins (for example jQuery) are a good example offering a 'prescribed' way to extension. The challenge comes with the open nature of JavaScript: there is nothing that prevents you from changing the internal functionality of any library or framework (see Monkey Patch pattern in the Modern patterns section to see how this is done). So, it comes down to coding discipline (keeping your team from modifying object internals) rather than being able to entirely close an object from modification.

Liskov Substitution Principle

The Liskov substitution principle states that derived objects should be substitutable for their base objects.

This relates to the interoperability of objects in a hierarchy of inherited objects.

Essentially it is saying that when extending a base object the original base functionality should remain intact.

An extension cannot change the functionality of the object it is extending. In reality it is not always easy to design objects this way,

because you cannot anticipate all possible ways an object will be used in the future.

Although JavaScript does not support classes, it does support inheritance (through prototypes), therefore the principle still applies. As a general rule, what you can do it keep your inheritance chains shallow and as simple as possible. The advantage of the Liskov substitution principle is that is makes your system more robust and less fragile.

One way to sidestep the issue of fragile inheritance chains (which is what Liskov tries to solve) is to limit the use of inheritance altogether and favor composition over inheritance. Interestingly enough, this advice actually originated from the Gang of Four. Object composition is where objects use services from other objects in what is called a 'has a' relationship. For example, a car object "has a" wheel object (in fact it has four), rather than a car and wheel deriving from a Movable base object.

Interface Segregation Principle

The interface segregation principle states the following: make fine-grained interfaces that are client specific.

This relates to the cohesion of an object's responsibility and related interface.

Essentially the interface represents a contract and this principle states that it should be unambiguous what it does and which clients it supports.

When multiple client types use an object with disperse methods, some of which are specific to a particular client, you are violating this principle.

The interface segregation principle promotes clarity, ease of use, and long term maintainability.

Although JavaScript does not support interface constructs, objects still expose an interface through which clients access the methods and properties of the objects. Well defined interfaces are critical to building robust and easy-to-maintain apps in JavaScript.

Dependency Inversion Principle

The dependency inversion principle states that you should depend on abstractions, not concretions, that is,

program against interfaces, not objects. This is a common notion in modern programming languages, but this principle is a little more

specific in that it also states that your application objects should not depend on lower level utility- or support-type objects.

If you program against interfaces (abstractions) and these lower level objects need change it will not affect higher level objects (if the interface stays the same).

The term dependency inversion comes from the fact that higher level objects are not dependent on lower level objects; rather lower level objects are dependent on the interfaces dictated by the higher level ones. This last principle is probably the least applicable to JavaScript because it lacks abstractions in the form of abstract classes or interfaces.

This concludes our review of the SOLID object oriented design principles as it applies to JavaScript. They certainly have applicability to JavaScript, except perhaps for the last one, the dependency inversion principle.

DRY stands for Don't Repeat Yourself. It is a simple, yet succinct principle: its aim is to avoid code duplication. Whenever you find yourself writing functionality that already exists somewhere else in your project, or worse, you cut-copy-paste this code, it is time to step back and rethink your approach. Usually you should factor the code out into a shared method, object, or module that exposes the necessary functionality which can then be shared across the project. This explains why DRY is also referred to as a Single Point of Truth; a very apt name indeed.

The DRY principle is also intertwined with to the notion of continuous refactoring in which developers constantly look for refinements and improvements in their code base as they develop or maintain the application. A common refactoring technique is to extract code and use object composition through which objects share functionality. Another is to adjust the inheritance hierarchy of objects to reflect a new way of thinking.

The goal of keeping your code DRY is a wise investment. It provides the opportunity to continually review and critique the entire code base for needless complexity and for missed opportunity for reuse. Over time many small DRY changes and refactorings will create significant gains in the overall robustness of your code base.

The Rule of Three is another principle. Essentially it is a milder version of DRY. With DRY, any duplication should be avoided. The Rule of Three states that under certain circumstances allowing two copies of the same code may be fine. The idea is that you should only start refactoring when the code is repeated three times, because only then the necessary abstraction becomes clear. This is best explained with an example.

Suppose you have a calculator object with a method called firstValue. It returns 1. Then you write another method called secondValue and it returns 2. You are thinking this is crazy, I want to keep my code DRY and I am not going to write thirdValue and have it return 3, fourthValue returning 4, and so on.

So you refactor and write a getValue(index) method. The passed in index value is returned as a number, like so: getValue(1) returns 1, getValue(2) returns 2, getValue(3) returns 3, and so on (indeed, the example is a bit silly but it will get the point across).

Anyhow, you ship your calculator and immediately your customers start complaining. The numbers are all wrong. It turns out that what they needed were sequence calculations that double the prior number. So instead of the sequence 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 they are expecting 1, 2, 4, 8, 16. What this shows is that two observations may not be sufficient to recognize a repeatable pattern that allows you to abstract it out correctly. Only after seeing three reference implementations can you be reasonably sure what the abstractions looks like; and that is the Rule of Three.

In this section, we covered numerous OO principles and other important coding rules. Understanding and internalizing these will help you become a better JavaScript developer and ready to take on design patterns and pattern architectures.