Best practices for handling errors in JavaScript.

JavaScript has built-in support for error handling.

Here we explore the commonly used best practices.

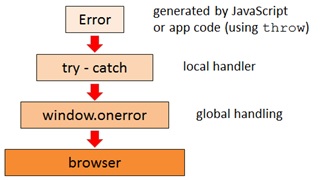

JavaScript has built-in support for error handling (also called exception handling). When an error occurs in the code, the JavaScript engine will create an Error object with an error message about the particular error and raises it (called throwing an error). Next, JavaScript will look for the nearest try-catch block and if it finds one the Error object gets passed to the catch block (called catching the error). Your code can decide how to respond to the error, but at that point JavaScript considers the error to have been handled.

If JavaScript does not find any try-catch blocks it will try to locate a global window.onerror event handler. If there is one then the Error gets passed to this handler and if not then the Error continues on to the browser. A return value of true in window.onerror means the error was successfully handled and the browser does not get involved. If false is returned the Error will continue on to the browser.

Graphically we can depict the error flow in JavaScript as follows:

JavaScript supports a number of built-in error types. The default error type is Error, but there are also 6 specialized error objects: EvalError, RangeError, ReferenceError, SyntaxError, TypeError, and URIError. If none of these are applicable to your project, then you can also create your own custom error type by extending the standard Error type.

JavaScript allows you to raise (or throw) your own error using the throw keyword, like so:

throw new Error("The start date is missing.");

Raising your own error will start the same error we saw before: flow of try-catch -> window.onerror -> browser.

As a developer you can catch and handle errors at two different levels: local and global. We will look at each in detail.

Local error handling

Local errors are processed by the nearest try-catch-finally block in which the error occurred. Here is an example:

try {

a = b;

}

catch(e) {

alert(e.name); // => ReferenceError

alert(e.message); // => 'b' is not defined

}

finally {

alert("I will always execute");

}

Run

In this example the try block will attempt to execute the code within its curly braces. It will fail because none of the variables are declared or initialized. The JavaScript engine will create an Error object with an error message and raise it (throw it). JavaScript will search the stack for the first try block and passes the Error object to the associated catch block. The catch block receives the Error object and starts executing.

The Error object has two properties that are supported by all browsers: name and message. In the above example the name shows ReferenceError which means that the error type is one of the built-in types. The message property contains the actual error message string.

The finally block is optional but if one is included it always gets executed -- irrespective whether an error occurred or not. A common use for finally blocks is to clean up resources, such as deleting an object instance or closing a server connection.

As mentioned before the exception is considered processed once the catch block has completed execution. In the code above the catch block displays the error type and error message which is not exactly a good example of proper error handling. Usually some corrective action is necessary which will allow the user to continue what they were working on.

There are cases in which you want to log the error, but, you don't want the error to be considered handled and just disappear. This is the case when you want to log the details of the error but no obvious corrective action is possible (by the way, error logging is discussed shortly). You can do this by re-throwing the error in the catch block like so:

var productId = 44;

try {

a = b;

}

catch(e) {

log(1, "Error: " + e.message + " Product: " + productId);

throw e; // re-throw the error

}

This is a common pattern. The advantage is that you can add contextual information to the log that is only available at this location such as the product the user was working on. This information would be lost if the error is handled at a later stage. Once the error is logged the Error immediately gets re-thrown. It then is handled by the next try-catch, window.onerror, or the browser.

Developers that are new to try-catch tend to overuse it because they mistakenly assume it makes their program more robust and fool-proof. This is not exactly true. The rule is that you only implement a try-catch block if the error can be corrected, that is, the user can continue what it was doing (ideally without realizing that anything was wrong). If not, there is usually no point in handling it. In fact, catching errors and not handling them will give the impression that everything is fine; but it is not and this can result in hidden bugs.

Sometimes you run into code that uses a try-catch block as a replacement for an if-statement, like so:

try {

process(); // May or may not exist

}

catch(e) {

// ...

}

This is not a good idea. First of all, the overhead of try-catch is fairly large and many try-catch statements may slow the program. Secondly, it gives the false impression that we are dealing with an unexpected exception which, in the example above, is not the case. It can easily be rewritten with an if statement that tests whether process is a function or not.

if (process && typeof process == "function")

process();

}

It is generally recommended to use try-catch sparingly and only when you are uncertain what conditions may occur, but you are certain that the code is able to recover from the error condition. An example would be invoking a 3rd part web service. If an unexpected error occurs you can try to re-connect and re-invoke but if that is unrealistic or not possible do not use try-catch.

Let's see how seasoned developers use try-catch. Analyzing the jQuery source code, for example, reveals that there are only about a dozen try-catch instances in roughly 10,000 lines of code. They mostly deal with browser and/or feature detection (typically IE) and many of their exceptions are handled silently, meaning there are no corrective actions taken in their catch blocks. The code looks like this:

try {

...

}

catch (e) { /* no action */ }

In the try block you may find code that attempts to access a certain browser specific feature. However, if the feature does not exist an exception gets throws. The code will then fall back to the default way of processing of whatever is was trying to do and nothing needs to be done in the catch block.

Next we will look at the throw keyword. Raising your own errors may seem strange because why would you purposely cause your program to fail? Let's take the example of parameter validation. Say you write an add function that adds two numeric values. In the function you verify that both incoming arguments are numeric and if not you raise a TypeError, like so:

function add (x, y) {

if (typeof x !== 'number') throw new TypeError("x is not numeric");

if (typeof y !== 'number') throw new TypeError("y is not numeric");

return x + y;

}

try {

alert(add(4, 5)); // 9

alert(add(4, "dog")); // Error

} catch(e) {

alert("Error: " + e.message);

}

Run

This will prevent anyone from calling add with non-numeric values, which in turn keeps your function from malfunctioning.

In response to the above function you may think that all add calls should be wrapped in a try-catch or else unhandled exceptions may occur, but that is usually not a good idea. A much better approach is to proactively validate the argument date before it gets passed to the add function.

If your application is both the producer and the consumer of the add function them the throw statements are probably overkill because you know the data that ultimately gets passed to add. However, if you are building a library or a public API that gets used by others then the above approach of validating the argument types and raising errors is highly appropriate. In these situations you have absolutely no control over what gets passed into the add function and you need to protect yourself against erroneous values. So, when throwing errors always consider who the end-user is.

Global error handling

Next we'll look at the global error handling with the window.onerror event handler. First off, note that this is a DOM handler

which is not part of JavaScript language itself. The window.onerror handler offers a last chance to handle uncaught runtime errors before they get

sent to the browser. As an aside, some older versions of Chrome and Safari do not support window.onerror, but more recent versions do.

All uncaught exceptions of an app are sent to window.onerror, so if you implement a handler expect to see a wide range of error types. In most cases there isn't much you can do to recover from these errors. At a minimum you should log the error to the server so you know what is happening on the client side of your app (note: error logging is discussed in the next section).

Three arguments are passed to onerror: an error message, the url of the file that contains the script, and a line number of the code where the error occurred. If onerror returns a value of true then JavaScript considers it handled. A return value of false means the error will be passed on to the browser which, depending on the browser and the error severity, may or may not display an error dialog. Here is an example of onerror that logs the error to the server:

window.onerror = function (message, url, line) {

log(2, "window.onerror: message: " + message +

"url: " + url +

"line: " + line);

return true;

}

Of course, you should never display the raw error message to the user which would create a bad user experience. In most cases you just silently log the error and then return true. For extra safety you may consider placing the logging operation in its own try-catch block to avoid triggering another unhandled error if the script or the connections are really messed up.

window.onerror = function (message, url, line) {

try {

log(2, "window.onerror: message: " + message +

"url: " + url +

"line: " + line);

}

catch (e) { /* do nothing */ }

return true;

}

Actually, an even better approach is to include the try-catch in the log function, because error logging is mostly not mission-critical. We will discuss this further in the next section.

Here is an example of a runtime error. It has an alert which you should never do, but this is for demonstration purposes only.

window.onerror = function (message, url, line) {

alert( "window.onerror: message: " + message +

"url: " + url +

"line: " + line);

return true;

}

execute(); // function does not exist

Error logging

It is important to log JavaScript errors to the server or otherwise you are really flying blind.

There is no other way to find out what is happening on the client in your app. A clever way to log to the server is with code similar to this:

function log(level, message) {

var image = new Image();

image.src = "log/" + EncodeURIComponent(level) +

"/" + EncodeURIComponent(message);

}

This code uses the fact that images can be dynamically retrieved from the server by providing a url (the src attribute). To log the error details all we need is a mechanism that triggers a method to execute on the server; and this does the job. The actual image object is never used and is immediately discarded.

The first argument in log is the level (or severity) of the error. Usually the value ranges from 1 to 5 with 1=fatal, 2=error, 3=warning, 4=info, 5=debug. Recall that we have seen the same log function being used in the earlier window.onerror function. It had the log function wrapped in a try-catch, but it would be better to include this in the log function itself so that errors do not cause other, possibly recursive, errors.

function log(level, message) {

try {

var image = new Image();

image.src = "log/" + EncodeURIComponent(level) +

"/" + EncodeURIComponent(message);

}

catch (e) { /* no action */ }

}

This version of the log function, may fail, but it never causes an error itself.

Another useful enhancement would be to create an asynchronous, non-blocking logging version of this function. This one will have minimal performance impact. Using jQuery makes this easy. It looks like this:

function log(level, message) {

try {

$.get ("log/" + EncodeURIComponent(level) +

"/" + EncodeURIComponent(message) );

}

catch (e) { /* no action */ }

}

Here is example of logging an error in a try-catch block.

try {

processData();

}

catch(e) {

log(2, " processData() failed. Error: " + e.message);

}

If the call to processData causes an error it will be caught and logged by our logging system. However, this example is most likely incomplete. As you know an error caught by a try-catch is considered to be handled by JavaScript. But in this case we only log the error and nothing else is done with it. This can cause hidden bugs. Perhaps this is okay but most likely something needs to be added: either a corrective action or a re-throw of the error in the catch block.

Errors and User Experience

The primary reason we have error handling is to improve the robustness and reliability of the code which, in turn, improves the user experience.

Applications that have errors are annoying and in today's marketplace users have no tolerance for shoddy apps. If an app does not appear reliable users

will walk away from it never to come back. As a developer you have pride in your work and of course you will not be satisfied when users are not happy with your work.

It also directly affects the bottom-line, so it is important you take error handling seriously.

There are two types of errors: non-fatal and fatal. Non-fatal errors are the ones you can recover from. These are mostly handled by try-catch blocks and in the ideal situation your code is able to recover to a stable state and the user never knew that something went wrong. As long as the user is able to continue their work, it is best to suppress any error notifications. If this is not possible then your error is probably of the fatal (or catastrophic) type.

Examples of fatal errors include: database not available, server not available, a web service that is offline, etc. The app simply cannot function without these and the user will not be able to continue their work. A good way to handle these errors is to immediately inform the user and attempt to reload the page.

Of course, your recovery methods and messaging to your user base also depends on the reliability and architecture of your servers, as well as that of the external web services. It is important that your user is informed about the error and possible ways to resolve this. In the worst case you explain a server is down and ask them to come back in the few moments and then try again. What you should avoid is to let the browser handle the error and show something over which you have no control. Again, when dealing with errors always consider the user experience.