Overview of JavaScript testing tools and techniques.

Many different JavaScript testing tools are available today.

Here we will explore two of the most popular ones: QUnit and Jasmine.

Testing is a large topic and a lot has been written about it. Having experience with testing in other languages will be helpful when starting out with JavaScript testing because many of the same principles apply. In this section we will review two of the more popular testing frameworks and how to use these in your projects.

Before getting into the details of testing frameworks we will first introduce the concept of Debug Mode which is an often overlooked aspect of testing (and tracing) your code.

Debug Mode

You will recall that the log function discussed earlier supports 5 levels of severity: 1=fatal, 2=error, 3=warning, 4=info, 5=debug.

The debug value (number 5) offers a powerful way to intersperse your code with debug statements that only get logged when the app is in debug mode (also called trace mode).

We will use a numeric logLevel variable which indicates the severity levels that are saved to the database. For example a 3 would save level 1, 2, and 3 errors (fatal, error, and warning), a 1 would save fatal errors only, and a 5 would save 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 levels (which is Debug Mode). Using logLevel offers a simple way to throttle the number of error message being stored in the database. In production you would typically limit it to level 1 or 2 whereas in production you could leave it at 4 or 5.

Here is the implementation:

var logLevel = 3;

function log(level, message) {

try {

if (level <= logLevel) {

$.get ("log/" + EncodeURIComponent(level) +

"/" + EncodeURIComponent(message) );

}

}

catch(e) { /* no action */ }

}

This works, but a better way is to place it in its own module and namespace to reduce your global footprint. Alternatively, place it in your own namespace to leave no additional globals at all.

var logging = (function() {

var logLevel = 0;

var log = function (level, message) {

try {

if (level <= logLevel){

$.get ("log/" + EncodeURIComponent(level) +

"/" + EncodeURIComponent(message) );

}

}

catch (e) { /* no action */ }

};

return {

logLevel: logLevel,

log: log

}

}());

Where necessary you can now intersperse your code with debug statements allowing you to trace the execution of your code. Here is an example of a complex multistep calculation:

logging.logLevel = 5;

function complexQuantumCalculation(start) {

logging.log(5, "Just before Step1: value = " + start);

var a = quantumCalculationStep1(start);

logging.log(5, "Just before Step2: value = " + a);

var b = quantumCalculationStep2(a);

logging.log(5, "Just before Step3: value = " + b);

var c = quantumCalculationStep3(b);

logging.log(5, "Just before Step4: value = " + c);

var d = quantumCalculationStep4(c);

logging.log(5, "Final value = " + d);

return d;

}

This code will log all intermediate calculation steps in the log database which can be double checked and validated. Once you are satisfied with the calculations you could possibly remove some of these level 5 log statements.

As an aside, it is important to have some utility or app that developers can use to quickly view, filter, and manage the log entries in the database without having to manually issue queries to the database.

Testing Frameworks

Determining which JavaScript testing framework to use in your project can be a daunting task: there are literally dozens to choose from.

Many of these are very good and at the end it comes down to personal preference. We will focus our discussion to two of the most popular ones:

a standard unit testing library called QUnit and a BDD (Behavior Driven Development) testing framework called Jasmine.

QUnit

QUnit was originally developed as part of jQuery, but a few years ago it became its own project with its own name: QUnit.

The jQuery Foundation uses it to unit test all their jQuery projects, including jQuery, jQuery UI, and jQuery mobile.

To use QUnit, download it, and include two files in your test pages: they are qunit.js and qunit.css. The js file contains the test-runner which gathers all the tests listed in the page and executes them. The css file contains the styling for the page that displays the test results. Your test page must also include two divs with ids qunit and qunit-fixture in which QUnit will place markup and test results. Finally, you include your JavaScript test scripts. Here is a basic test page:

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>QUnit test page</title>

<link href="/css/qunit.css" rel="stylesheet" />

<script src="/js/qunit.js" type="text/javascript"></script>

</head>

<body>

<div id="qunit"></div>

<div id="qunit-fixture"></div>

<script>

test("my first name test", function () {

var name = "Mary";

equal(name, "Mary", "We expect Mary.");

});

</script>

</body>

</html>

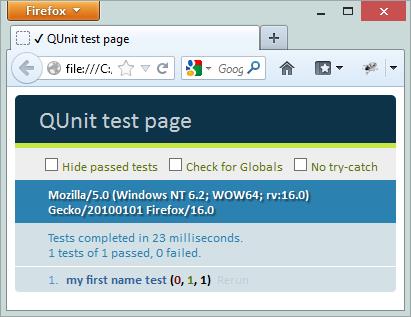

Run this and you'll get the following output:

The page shows that the test was successful. Next we are changing the name and run the equal assertion again, which will fail:

test("my first name test", function () {

var name = "Mary";

equal(name, "Mary", "We expect Mary.");

name = "Thomas";

equal(name, "Mary", "Again, we expect Mary.");

});

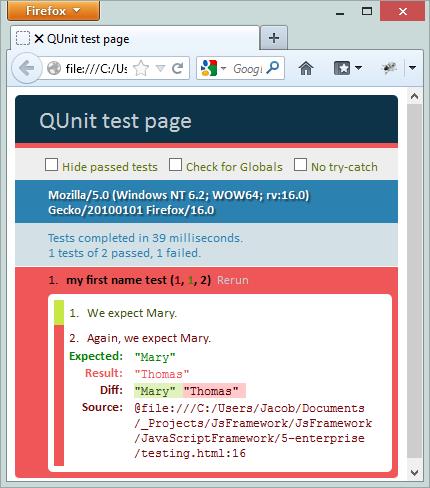

Run this and you'll get the following output:

Let's examine the actual testing code. The test function in QUnit accepts two arguments: a name for the test which shows up in the test results and a function with the actual tests which are expressed by one or more assertions. QUnit supports just three assertions: ok, equal, and deepEqual.

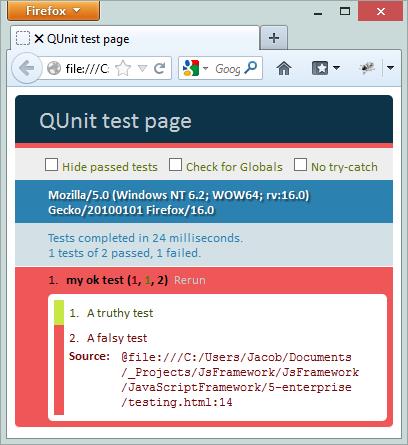

The most basic is ok which accepts a single argument. If this argument evaluates to truthy then the test succeeds and a falsy outcome fails the test. An optional message can be added as a second argument. Here is an example with results:

test("my ok test", function () {

ok(true, "A truthy test");

ok(0, "A falsy test");

});

Run this and you'll get the following output:

Another assertion is equal in which an actual value is tested against an expected value. Internally this uses a simple comparison operator (==) which has its limitations because of implicit type conversions. Like ok, an optional message can be added as a third argument. Here is an example where the output of an add function is tested:

function add(x, y) { return x + y; };

test("my equal test", function () {

equal(add(3, 4), 7, "Function add 3 + 4 test");

equal(add("11", 28), 39, "Function add 11 + 28 test");

});

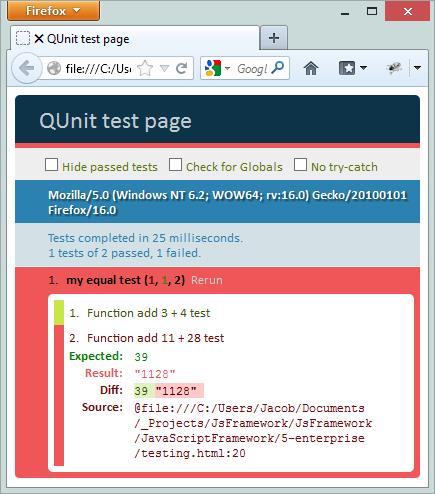

Run this and you'll get the following output:

The second test failed because we passed a string value to add rather than a number.

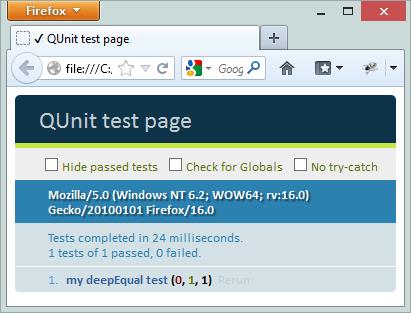

If you need strict comparison use the deepEqual assertion. It uses the strict comparison operator (===) and it performs a deep comparison of objects, functions, arrays, etc., meaning it goes through each object's name/value pair even in deeply nested hierarchies. In general deepEqual is preferred over equal. Here is an example:

test("my deepEqual test", function () {

var jim = {

name: "Jim",

address: {

street: "123 Main",

city: "Houston"

}

};

deepEqual(jim, { name: "Jim", address: { street: "123 Main", city: "Houston" } },

"Jim deep instance test");

});

Along the top of the test page there are three checkboxes that are helpful in focusing on the test results. The 'hide passed tests' suppresses the display of any successful tests so you can concentrate on the problems only. The 'check for globals' performs a before and after test on the global window object. If it finds that your code has left a global variable or object behind it will tell you so. Finally, the 'no try-catch' will perform tests without a try-catch context so any failed test will cause the test-runner to stop. The advantage is that you get to see the browser's native error messages which may be helpful with older browsers.

QUnit offers quite a bit more functionality than demonstrated here, but this will give you a start in building unit tests for your JavaScript code.

Next we will review Jasmine which is a BDD (Behavior Driven Development) testing framework. It is rather different from QUnit.

Jasmine

Jasmine is a BDD testing framework. What is BDD? BDD is an extension of TDD which stands for Test Driven Development.

The basic idea of TDD is that your development cycle is test-driven, meaning you write your tests before you actually start writing code.

Doing it this way forces you to think upfront about your program's design, structure, and API rather than just starting off coding.

Experiments have shown that the resulting code is usually markedly different (and better structured) from what would have been produced otherwise.

There are some limitations with TDD which BDD tries to address. For example, TDD does not tell you what should be tested and how. The focus in BDD is testing the desired behavior of the software, that is, those elements that add business value by concentrating on the requirements and user stories that need to be implemented by the code. A full discussion of TDD is beyond the scope of this discussion but we will be able to show you how to setup some basic Jasmine JavaScript testing.

Jasmine does not require the DOM, so it can run without a browser. Many different environments are supported, such as .NET, Java, Ruby, node.js, etc. This allows Jasmine tests to easily integrate with a Continuous Integration (CI) environment. In the case of QUnit, you need to open the browser, run the tests and wait for them to complete (there are ways to integrate QUnit into CI, but they are more involved). When using Jasmine with CI you always have access to the latest builds and you get regular feedback on the state of your automated tests.

For demonstration purposes we will keep it simple and run the Jasmine tests in the browser. Let's get started writing a simple test:

describe("Javascript built-in functionality", function () {

it("concatenates two strings together" , function () {

expect("Hello " + "Test").toBe("Hello Test");

}

}

The syntax of Jasmine is clean and feels natural which makes it easy to use. Notice how the above code almost reads like a sentence: "Describe JavaScript built-in functionality: it concatenates two strings together". Next you state what your expectations are: in this case, you expect that concatenating "Hello " + "Test" to be equal to "Hello Test". Again, it reads like a sentence: Expect "Hello " + "Test" to be "Hello Test";

Let's examine the functions involved. With describe you start a test suite. It can have multiple it functions and all of these together are called a suite. The it function declares what is called a spec which consists of a short description of a test and a test function. Within the test function you are testing a value or expression that is passed as an argument into expect. The argument is called the actual. Then finally, the chained toBe method contains the expected outcome. The toBe method is called a matcher which matches the actual value against the expected value. Jasmine offers many different matchers, some of which we will see later in this section.

Using Jasmine in the browser requires that you download the "standalone release" of Jasmine. You need to include three files (one css and two js files) and an immediate function with Jasmine startup code in your test page. At that point you are ready to start building your tests. The code below shows where to place the code to be tested and the specs (tests). There is no need to put anything in the page body because Jasmine will fill that out for you.

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Jasmine test page</title>

<link href="/css/jasmine.css" rel="stylesheet" />

<script src="/js/jasmine.js" type="text/javascript"></script>

<script src="/js/jasmine-html.js" type="text/javascript"></script>

<!-- Your code and specs go here -->

<script type="text/javascript">

(function () {

var jasmineEnv = jasmine.getEnv();

jasmineEnv.updateInterval = 1000;

var htmlReporter = new jasmine.HtmlReporter();

jasmineEnv.addReporter(htmlReporter);

jasmineEnv.specFilter = function (spec) {

return htmlReporter.specFilter(spec);

};

var currentWindowOnload = window.onload;

window.onload = function () {

if (currentWindowOnload) {

currentWindowOnload();

}

execJasmine();

};

function execJasmine() {

jasmineEnv.execute();

}

})();

</script>

</head>

<body>

</body>

</html>

Now that we have a skeleton test page we are ready to write a test. In our case we are going to build a calculator. It is a simple, but fully functional calculator that supports chaining, like so:

var calculator = new Calculator(); alert(calculator.add(20).sub(5).mul(2).div(5).get()); // => 6

Since we are using BDD we will write our tests before implementing the calculator. Our calculator will support 4 basic operations: add, sub, mul, and div and two helper methods: get, which returns the current value, and reset, which resets the calculator back to zero. As mentioned before, all operations will be chainable.

Here are the Jasmine test suites and specs:

describe("Calculator", function () {

describe("Simple method calls", function () {

var calculator = new Calculator();

it("adds a number", function () {

expect(calculator.add(13).get()).toBe(13);

});

it("substracts a number", function () {

expect(calculator.sub(5).get()).toBe(8);

});

it("multiplies a number", function () {

expect(calculator.mul(4).get()).toBe(32);

});

it("divides a number", function () {

expect(calculator.div(2).get()).toBe(16);

});

});

describe("Chained method calls", function () {

var calculator = new Calculator();

beforeEach(function () {

calculator.reset();

});

it("adds, substracts a number", function () {

expect(calculator.add(13).sub(8).get()).toBe(5);

});

it("adds, subtracts, multiplies, divides a number", function () {

expect(calculator.add(6).sub(1).mul(4).div(2).get()).toBe(10);

});

});

});

We have a test suite called 'Calculator' with two sub suites: one to perform single operations and another to perform chained operations. It is perfectly fine to have nested suites. In fact, this is common practice as it allows you to structure your test suites in a way that works best for your projects. Notice that the JavaScript function scope rules apply, that is, nested functions have access to their parent's variables and properties, so the it functions have full access to all of describe's variables.

The 'Simple method calls' suite has 4 specs, each one testing a different operation. Between the it functions the calculator is not being reset, so each calculation builds upon the prior test. This confirms that all nested it functions have access to a shared calculator maintained by their parent describe function.

The 'Chained method calls' suite has two 2 specs, each one testing a chaining operation. In this situation, we like to reset the calculator between the specs. Jasmine offers a beforeEach and afterEach method that gets called before and after each spec. We prefer to reset the calculator before each test, so this is what we use. The two specs test chaining of two and four levels respectively.

It is now time to write the calculator:

function Calculator() {

var total = 0;

this.add = function (x) { total += x; return this; };

this.sub = function (x) { total -= x; return this; };

this.mul = function (x) { total *= x; return this; };

this.div = function (x) { total /= x; return this; };

this.get = function () { return total; };

this.reset = function () { total = 0; };

}

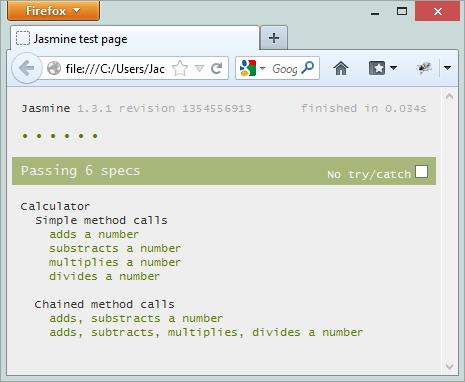

With the calculator and the specs in place we are now ready to run our test suite.

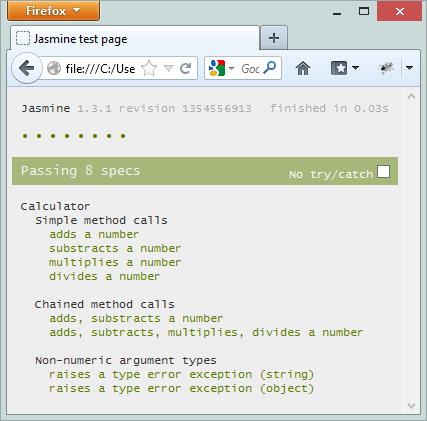

Run this and you'll get the following output:

That looks good: all specs passed. Jasmine has a clean interface. Most items on the page are links which allow you to drill down and navigate through all suites and specs. By the way, when you click on the 'Simple methods calls' Jasmine will run the specs individually which will fail for the second, third, and fourth because they depend on prior computations (as explained earlier).

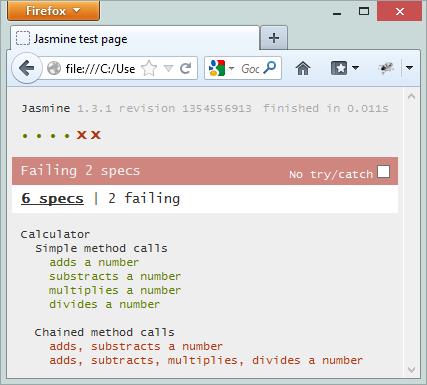

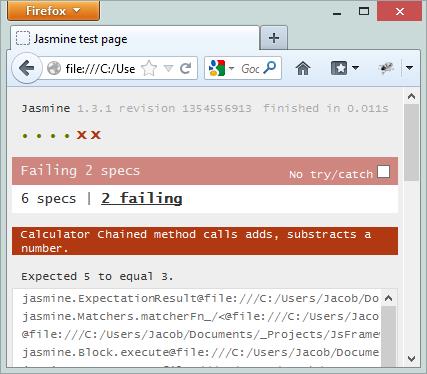

Let's create a couple of failing tests. Here is what a failed test result looks like:

Run this and you'll get the following output:

This shows the summary of all 6 specs. Details are visible by clicking on the failing links or the '2 failing' link at the top. In one of the cases it expected a value of 5 but the actual value was 3.

Next we will look at some additional matchers. We have already seen toBe. The more common ones are: toEqual which compares literals, values, and objects, toMatch which finds a match by using regular expressions, toBeUndefined which compares against undefined, toBeNull, toBeTruthy, toBeFalsy, toContain, toBeLessThan, toBeGreaterThan, and toThrow. All of these are fairly self-explanatory. We will look at toThrow in some more detail as this is an important matcher for testing expected failures.

Suppose that we like to tighten our Calculator a little by ensuring that only numeric arguments are used in the operations. If the value is non-numeric then we raise a TypeError exception. Let's first write a Jasmine suite to test this new functionality:

describe("Non-numeric argument types", function () {

var calculator = new Calculator();

beforeEach(function () {

calculator.reset();

});

it("raises a type error exception (string)", function () {

var fn = function () {

return calculator.add("Sixteen").get();

};

expect(fn).toThrow("non-numeric value");

});

it("raises a type error exception (object)", function () {

var fn = function () {

return calculator.add({ city: "Miami" }).get();

};

expect(fn).toThrow("non-numeric value");

});

});

This is fairly similar to the prior suites, but notice that the calculator calls are wrapped in their own function. This function is then passed into expect. This is necessary or else expect won't be able to properly catch the exception.

Next we have to adjust the Calculator and include the argument check.

function Calculator() {

var total = 0;

this.add = function (x) { numeric(x); total += x; return this; };

this.sub = function (x) { numeric(x); total -= x; return this; };

this.mul = function (x) { numeric(x); total *= x; return this; };

this.div = function (x) { numeric(x); total /= x; return this; };

this.get = function () { return total; };

this.reset = function () { total = 0; };

function numeric(x) {

if (!isNaN(parseFloat(x)) && isFinite(x)) return;

throw new TypeError("non-numeric value");

}

}

Each operation includes a call to numeric which is a local function that checks whether the incoming argument value is numeric. If not it raises a TypeError exception with a message string "non-numeric value". It is this specific error message that Jasmine will be looking for in the toThrow method.

When running this test we are getting the expected results.

Run this and you'll get the following output:

Jasmine matchers also have the ability to test negative cases by chaining in a not between expect and the matcher, like so:

expect("Hello " + "Test").not.toBe("Greetings Spec");

Finally, we will look at custom matchers. They are easy to write and easy to add. Suppose we want a matcher to confirm that a number is positive. Let's call it toBePositive. You can add your custom matcher to a beforeEach with a call to this.addMatchers using this.actual. Here is an example:

beforeEach(function () {

this.addMatchers({

toBePositive: function() {

return this.actual > 0;

}

});

});

And here is how it is used in our spec:

describe("Positive/Negative tests", function() {

var calculator = new Calculator();

beforeEach(function() {

this.addMatchers({

toBePositive: function() {

return this.actual > 0;

}

});

});

it("returns a valid positive value", function () {

expect(calculator.add(3).sub(1).get()).toBePositive();

});

it("returns a valid negative value", function () {

expect(calculator.add(3).sub(9).get()).not.toBePositive();

});

});

Notice how we are using the new matcher to test for positive and negative numbers by chaining in the not operator. This is very convenient and it prevents us from having to write a separate toBeNegative matcher.

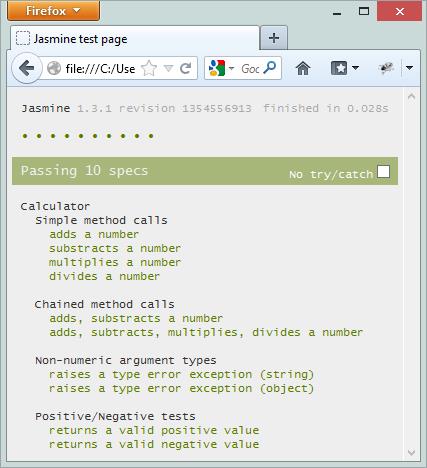

These are the results:

Run this and you'll get the following output:

Jasmine offers more than we have shown here, but hopefully these and the other examples have given you a sense of the maturity and richness of the JavaScript testing tools available.